The latest game the Old Men team played was DEATHMATCH ISLAND by Tim Denee (now working on Blades ‘68), and based on the Paragon System, by John Harper (Blades In The Dark, AGON) and Sean Nittner (AGON). It is a very handsome book with an intriguing premise: you have been selected to participate in an event that will lead to fame, freedom, and unlimited wealth. “A deadly game show set on a chain of mysterious islands.” And so we embarked under an imaginary sun to find out whether we would ultimately Play To Win, or to Break The Game.

Yes, there are many mysteries to DEATHMATCH ISLAND. The most mysterious of them is what happened to the Mysterious Third (Chris), the silent partner of our tripartite reviewing panel? He was nowhere to be seen. Is that simply so that our Threedom title never makes sense? Or is this also part of this “Paragon System” of which you speak? Let’s gather the dicepools of clear reporting and critical thinking and find out!

Jim: We should probably start with why you chose this game, Kieron? And where is (Chris)? Explain it to me like I’ve just woken up on a boat with no memory of how I got here.

Kieron: Chris was off on a mysterious adventure, so we decided to grab the chance to play a game when he was away, in real life (ours), with real human beings (yours), in a real house (mine). We grabbed Deathmatch Island because it seems like something we like anyway, at least conceptually, but I’m also working on a Paragon system hack myself. I’d played AGON, I hadn’t played this – despite having read it and drawn from it already. So there was a lot in there I wanted to see how it worked at the table – because it really does take the Paragon system and tweak it in meaningful, detailed, ballsy ways, while still being very much the same beast.

The Paragon system, as introduced in Harper/Nittner Odyssey-’em-up AGON is about a group of competitive individuals working towards a common goal. While you’re a team, you’re also looking for individual glory. “Who is best?” is a fundamental question in the game, and the mixture of storygame and competition gives its own specific vibe.

Jim: ‘Who is best / i am best!’ became the comic mantra of our AGON play, but is absolutely both totemic and actually the rules.

Kieron: Yes. This system resolves its challenges via a dicepool system where players roll to gain narrative authority, The GM – the Production Player, in Deathmatch Island – gives a total, and players try to beat it, with the narrative football passing in order of ascending scores. If you don’t beat the score, you go first and narrate how you fail. If you beat it, you describe how you overcome the challenge, and set it up for a final defeat. If you roll highest, you describe how the challenge is vanquished. This is interesting for a bunch of reasons, but mainly in how it compresses a lot of story into a single contest. In Agon, it could be “Does the Cyclops crush the village?” In Deathmatch Island, it’s “How does everyone do in the challenge where you’re all trying to get across the lava?”

We’ll get deeper into how Paragon works, but it’s worth noting that Deathmatch Island really does make a lot of small, meaningful changes to it. Some of these are for the theme of the game, but others are ones which I read and decided to lift for my own work. If I was running Agon again, I’d likely work them back in. In Agon, you only lose the “health” resource if the conflict is “dangerous”. In Deathmatch Island, you always lose fatigue – but if it’s dangerous you lose its “health” instead, which is normally only lost after fatigue is depleted.

Jim: Immediate interesting choices for the players.

Kieron: As such, all challenges have at least some mechanical stakes. In Agon, during the big-multi-challenge climaxes, the penultimate stage let the winner pick the domain (as in, the stat you use) of the final challenge – which mean it’s really difficult to give a climax a narrative shape, as it could be anything from a fight to a singing contest. In Deathmatch Island, the penultimate stage lets you pick which domain you get to ALSO add to the climax challenge for free – which is mathematically nearly identical, but grounds the fiction more. Most basic and charming, Agon has a system that when you hit certain injury thresholds, you gain an advance – among other things, a neat way to give the players doing the worst a boost. Deathmatch Island has the same system, but also prompts each player to gain an in-story scar when they reach it. As in, it grounds this advance in the fiction rather than just being an untethered level-up. You know this guy is a bad-ass. They’ve got an eye-patch. This is beautiful stuff.

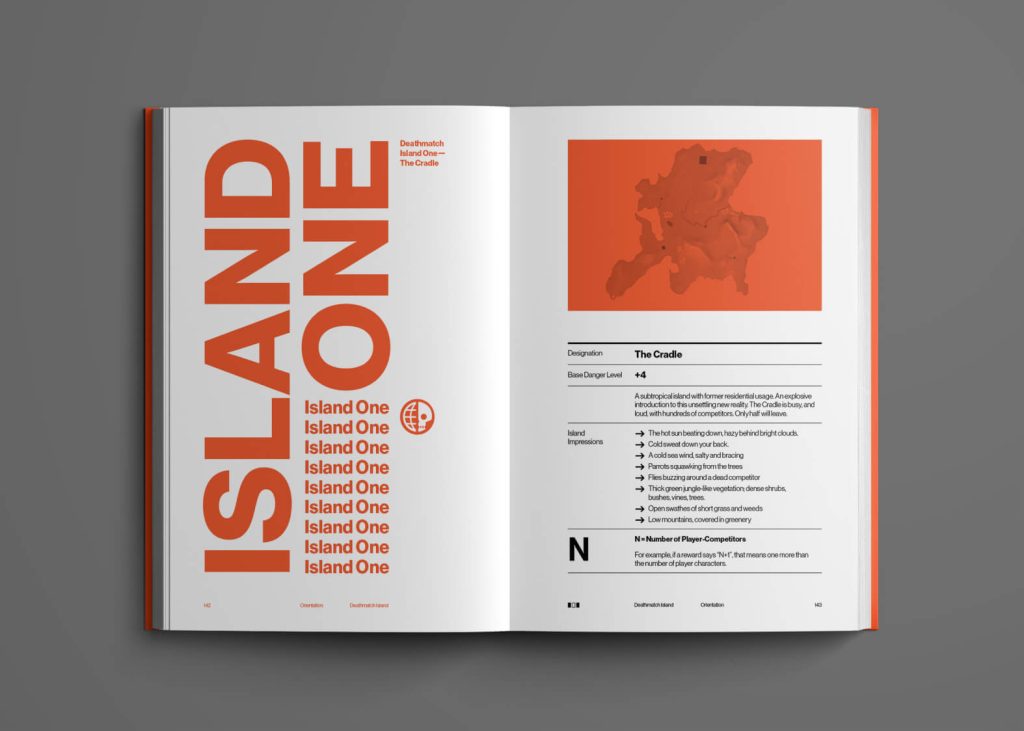

Deathmatch Island is also literally beautiful. We’ll be talking about Denee’s game design a bunch, but it’d be amiss if we didn’t hit up the visual design first.

Jim: That, at least, is super true, Kieron Gillen. Deathmatch Island is DESIGNED. Denee is someone who really knows how to make things look polished and professional on the page, and I am not sure I own many books where the competency of things like page-design and making tables really fucking work good is quite as clear cut. It’s very Orange and White. It feels like something created with an incredibly specific vision in mind. The book, particularly as a physical object, captures the vibe so completely that it’s hard to imagine it being any other way. Triangle Agency does some similar stuff, but what’s here is more austere, sober, and disturbing, even while it is playful. To be sure, there are lot of incredibly pretty, high production value books right now, and this is not a book that is based on how good the illustrations are (they’re abstracted, and again, designed: a simple depiction of a grenade, a can of beans and so forth) all of which sells the corporatised, labelled, produced nature of the game as a fiction. This is a TTRPG where the GM (and by extension the forces that are causing the Deathmatch Island event to happen, whatever they might truly be) are literally called Production. It has the faceless, mysterious, moderately threatening banal alienness of big corporation stuff that occasionally appears in modern fiction. And to convey that in the visual design is masterful. It also evokes The Prisoner and 1960s weirdness, and it also spoofs modernity and the logic of corporate signage. We talked a bunch about how that vibe extends to the rest of the game, right?

Kieron: Oh yeah. While I was mainly running this to see what it did to Paragon, the second it hit the table, I was absolutely in its power, trying to get it. I especially like how it grounds the game in its weirdness with things like the hand-outs – passing the players these blandly enthusiastic corporate-training influencer documents. The icebreaker questions, where characters get to give little bits of flashback to their lives. I especially like the Theorise stage, where the characters try and work out what’s going on, and depending on what they believe is true, unlocks options on the GM side to feed into these beliefs.

As such, the game we played was definitely towards the weird-fiction end of it – we’re all The Prisoner-heads, and so it got increasingly meta. I’m sure with a group with different loves it would have become more of a political project, or a reality TV parody, or whatever.

Deathmatch Island is interested in the ironic tone throughout – the contrast between one thing (the horrible violence) and the other (the sanitised branding). I love this kind of stuff – I instantly knew that I would be running it with a theme tune, that I’d play when people arrive on the island and play again when we reached the final deathmatch climax of the island.

“When you next hear the Hustle by Vin McCoy, the deathmatch begins. Play to win!”

Jim: That tune is still going round and round in my head now, so it was a good choice.

Kieron: I did smile when another player said it got played at their new year’s party, and definitely changed the mood for them.

Jim: In fact I’ve spent the last two weeks listening to nothing but disco, so there’s something deep awakened in me by the time we spent on this. And it wasn’t always playing to win? In the end I played to break the game. But before that, we should probably get into some details about how it played as a player. One of the things that I liked most about AGON was that after 15 minutes of character creation we felt like Greek heroes lost in a mythic Mediterranean. I think, as mentioned a couple of paragraphs ago, the possibility space is wider here. The game provides matching uniforms which can be blazers and proper trousers, or a jumpsuit. And the character creation is very much “real people”. I was a corporate trainer, for example, while Old Men Friend Olly was a piano teacher. The challenge-type dice lean into this, too: Social game, Snake game, Challenge Beast, Deathmatch, and Redacted don’t make up traditional personal stats as such, but instead represent numbers we can match with the narrative. My character’s personal journey being from Social character to Deathmatch lad was particularly entertaining, I thought. Corporate softness giving away to an “I’ve watched Rambo First Blood fifteen times” LARP posing. Which of these dice gets invoked is about the type of challenge we face, but also can be combined with others if we want to spend the Fatigue currency, and also with Advantages which emerge from flashback narratives. (And these are burned, a one-off moment of inspiration that is applied to give us a dice at the GM’s discretion. Getting a D6 because your advantage is not actually all that relevant stings, but it is still an advantage!)

Kieron: I thought I would not like this, but actually was really pleased with how it worked. As you say, it being very linked? Big advantage, but D6 is still not nothing. Though it does make me think about one of the sticking points of the Paragon system – in terms of the dice pool assembly. You’re meant to declare it in game, unattached to the fiction in any way, except with each player deciding if the dice apply. In Deathmatch Island, its suggestion is the on-screen text chyron – like “Trevor the Accountant, with a symbol of a machinegun popping up”. Except when learning it players always want to ask questions (or prompting if they forget) and it’s all running on the honour system anyway (as players aren’t punished if they fail to include relevancy of any of the dice when they narrate). That this advantage system is based on a question does seem to break this structure too, and seems to implie that it’s always a bit of a sticking point.

Of course, there’s also the core dice, those dice you always get.

Jim: You always get your name, because that’s the core of this thing. It’s about fame! You’re on television! Probably.

Kieron: Oh – a minor thing I dig? When you increase your name dice due to increasing fame, the other players pick a nickname for you. That’s golden.

Jim: This is all very satisfying because constructing a dice-pool is one of the inherently satisfyingly crunchy parts of playing such games. And it is pretty satisfying as a player, even though not all the postures it wants you to take on are instinctive: we stumbled over flashbacks and testimonials, for example, because the structure is not quite what we have become trained to expect from TTRPGs. I don’t think that hurt my experience of it particularly, but it was notable that when things clicked (particularly the “we all contributed but I was best” moments of telling the story of what happened) it began to sing. In fact, we probably ended up not quite getting to the point where that was second nature, and I wonder if the second run of things could have made that work. Because this IS meant to be played as a second run, right?

Kieron: Yeah, second time and even more. The core game is three islands, ending up at the end of the season… but then it loops. You can come back as surviving contestants, or new contestants – and there’s aspects of the game which essentially unlock on a later play through, with some equipment being passed onto your successors, like the secret maps. Each of the Islands is big enough that you shouldn’t see more than a third of any one on any one trip through – and the GM also has different casts of contestants to throw at you, with their own different tones. I deliberately chose one of the most standard grounded ones, but there’s other casts where the weirdness of the game starts to leak in even more specifically. There’s lots of game here, even without touching on the extra-stretchgoal content. The Love Island inspired Island was calling me hard…

No matter what, the game is always building towards that last island, where the 200 contestants are strimmed down to a handful and everything is very much Deathmatch On An Island.

Jim: This is the bit we didn’t get from AGON, right? The actual showdown between the characters. The Paragon system leans towards “we’re all on the same team”, but there’s a player of the match, here it’s a little more cut-throat. As it says on the (corporate branded) tin, it’s Deathmatch. There’s a decision to be made at the end. The final island is one where all the surviving contenders are pitted against each other, and that means the players, too. Of course the Theorise phases, redacted areas, and access to weapons that can be used against Production mean there’s another option: to try and break the game. Whatever the reality you’ve theorised, you can decide to attack and not go into that night purely for numbers.

Deathmatch Island handles this cleverly by getting each of us to fill out a little card/form, privately, to say whether we are playing to win or trying to break game. We perhaps didn’t make quite enough of the discussion beforehand, as to what our characters were going to do, and whether their journey had been one that bonded them closely enough for mutual murder to be impossible, but even so it became quite dramatic. Two of us elected to break the game and one went for the win. (And I should say that my motivation here was at least in part to do with my character’s theorising that if it was a show or a simulation then to go along with the script and not attempt to do something unexpected was going to be to fail the challenge of it overall, even if you won the Deathmatch.) The character that goes for a win gets an advantage in the final battle, and in our case the two pushing to break split up so that there was a battle between win-wanter and the breaker, and then a final scene between in the surviving breaker and the win-wanter. This was hugely dramatic, I thought, and not just because I have saved my rocket-launcher for the end. It was dramatic because of what Deathmatch Island does that’s different to the other Paragon games, not just in pitting the players directly in PvP stuff, but in allowing that to unfold with a question of “is it over?”

Kieron: Absolutely. I love all this stuff – like, the theatre of filling in the form and reveal? Absolutely my jam. Turning this slow-boil competition into open conflict? Oh yes. But what I find most interesting is that how, in this moment when characters are literally trying to murder one another, it’s actually Paragon at its most co-operative.

It really does come down to the “Is it over?”

The last conflict is exactly the same as always, but after the winning player narrates how they win, the loser is asked that question. Is it over? If yes, that’s the end. If not, they describe how they escape that, but set themselves up for another downfall. The winner describes the ending, and asks again? The process repeats until the loser accepts this really is over.

Now, when I read it first I was reading it as a way to ensure that the ending was a compromise, to ensure the winner just didn’t have agency to stomp it all over their rivals. While it is that, that’s not what it’s really for. It’s about creating this back and forth.

“I shoot them, riddling them with bullets. Is it over?”

“No. I take a bullet, but drop behind cover, returning fire.”

“I crawl closer, bullets bouncing around me, and throw a grenade, which bounces in front of you. Is it over?”

“Hell no. My eyes go wide and I try to escape, and am thrown through the air towards you. I’m at your feet, and reaching for you with my knife.”

“I’m surprised, and you’re on top of me with the knife. We’re face to face and I’m screaming at you. I manage to roll over and the knife bursts through you. Is it over?”

In Paragon, a player has agency to narrate – but this extends the key, most important bit in the whole game, to a cinematic back and forth… but the decision is already finalised. Everyone knows the score. Now we see how it goes down.

That’s what the Paragon system really does at its core. The dice have fallen, we know the shape of what happens – now by passing the narration we get the specifics. The climax really is paragon as its best, and it sings when players are working together even as their characters are competing. Good play in paragon isn’t just describing how things are going for your character – it’s also thinking about who’s following you, and setting them up for something. It’s a game that really is about teamwork.

That’s why the Paragon system is a tricky one, in many ways – it’s a skill folks aren’t necessarily coming to the table with. Thinking leans too atomic, but I think Deathmatch Island really does do a lot to try and ease people into that. Even the fact the looping of the game lets the players think about how they can do things next time around. Was our deathmatch ending perfect? Hell, no. But the three sessions to get there were quick enough to make us all be pretty much aware that if we played on, we’d have been really cooking.

Jim: Speaking of cooking, I found myself wondering what Paragon games look like from here. You are making something using this ruleset. Hell, Harper just announced Ride Or Die, which is a “simplified” version based loosely on the Fast & Furious movies. It feels like WHO IS BEST really does have a future. Does Deathmatch Island, as you seemed to imply upthread, help confirm that these are correct decisions in terms of using this system to make new games?

Kieron: Well, in our random sampling of game designers, Nittner, Harper, Denee and myself are working on Paragon games, and only you not, which means that 80% of all game designers are working on Paragon games. My sampling is perfect, do not question it.

I think Harper simplifying with Ride Or Die speaks to something of the direction. Paragon works best when players just know it. A challenge is called, everyone assembles their own dice pool, and rolls. They look at the results, and narrate in order. If everyone knows the game, that could be invisible at the table. As it is, Paragon games stumble until that point – in our long Agon campaign, I don’t think we ever got there. So working ways to streamline seems the way to go, to make it easier to internalise and reach that point – if only to teach people Paragon, so they can then be more comfortable with a heavier game. I’m certainly doing some streamlining of my own with my thing.

But I also don’t think you need to wait – Deathmatch Island really is a great way to try Paragon. Of all the smart things it does, that it works in a one off (one island) or a short campaign (3 sessions, three islands) is one of the smartest. You can get a genuine narrative adventure, in this fascinating system, with unique vibes, with a minimum of commitment. A deathmatch isn’t for life.

Lost in the hills of Somerset, this Rossignol searches for meaning among the clattering of small plastic bones.