This is Threedom, our review series in which forever-GMs Jim Rossignol, Kieron Gillen, and The Mysterious Third (Chris) get to spend a bit of time as players as we deliver each other delicious fresh campaigns of the TTRPGs that have most arousingly intrigued us and inspired us to action. Have a read of our other Threedoms here.

This time we were also joined by a fourth member — just to make sure the naming convention doesn’t make sense for even a few instances of the series — the designer, writer, and Minecraft-manager, Alex Wiltshire.

Together we’ve just completed a campaign of Carved From Brindlewood gothic horror RPG The Between!

It was fucking great!

Jim: The Between is a game of mysterious monster hunters blessed with strange powers dealing with horrible mostly-supernatural threats in Victorian London. The plot culminates in a showdown against what the game describes as a “Moriarty-style” mastermind. But I don’t recall Moriarty having access to quite as much of the national infrastructure or, indeed, interdimensional magic, ghosts, vampires, mirror-demons, or any of the other wild shit that we ended up dealing with. And there is a LOT of wild shit in this game. Kieron, the menagerie of crazed supernatural stuff isn’t actually why you wanted to run this game for us, is it?

Kieron: Oh, there were a bunch of reasons. I’ve been following its development for years – The Between was the full game which Jason Cordova was working on before spinning off its mystery system into Brindlewood Bay to test whether you could do a game which worked with its postmodern mystery system where solutions are constructed by the players and their truth determined by the dice (Spoilers: you could do this.) And then they took that honed version back into the original game to let it mix with all its other stuff. What I was mostly interested in seeing how the other stuff cooked.

As a side point, from my years in videogames, I always remember learning to be twitchy around a project that tried to innovate in a big way in two separate areas, because they could never actually test anything for real until they had at least one working properly. I think Cordova made a smart call.

I’m almost surprised I’m running it because the setting isn’t an instant turn on for me. The main influence is Penny Dreadful, a show I watched with mixed feelings: some stuff I adored, but broadly felt it was a peak exemplar of that period of streaming when forty-minute shows were bloated to an hour. Still, Eva Green witching it up with the best of them, who wouldn’t want that? In our case, it was literally wanted, as Chris grabbed the Vessel playbook, clearly based on Eva’s scenery chewing glories.

It’s really this larger structure I was interested in seeing play out. Gauntlet Publishing are doing an interesting thing in pursuing what I think of as semi-cooked adventures. Trad PbTA often builds from nothing, or a perhaps starter. Trad (er) trad has those huge tomes that you need to annotate to run. This sits between the two – an easy way to think is its “Threats” are like the notes one would make from a full adventure, but deconstructed. A cupboard of stuff for a GM to pick on and assemble appropriately. Palettes. Or a fridge and a spice cupboard.

So The Between is doing that… but it’s also doing a lot more than the modularity of Trophy or Brindlewood Bay. It’s running multiple of these fuckers at once. You add Threats on top of each other, so it’s got a larger structure playing out, unlocking aspects as you play. It’s also got these little interesting bits of narrative tech I wanted to see play out: the Unscene, the character-backstory-as-cutscene of the masks, and more. Plus how the Brindlewood Mystery System is integrated, and turned to very different purposes. We’ll get to all that, I’m sure. Or maybe not. We have a lot to talk over.

But I want to start with the absolute basics – the characters. They’re glorious. What was your first impressions of them? Hell, the game generally.

Jim: Well, the first thing I remember was us marvelling at the character keeper you dug up, and how it automatically assigned the manservant playbook (The Factotum) to my character (The Undeniable, which I will get into in a bit) so that an immediate social and class hierarchy was established. Victorian vibes in Google Sheets. Impressive stuff. But I’m also currently super interested in games that assign specific social roles to people (“who is the leader” type decisions) so to see that click into place magically, well, that instantly commanded my attention.

The playbooks say a lot more than that, however. What’s striking about them is the extent to which they’re authored. (That term again.) I think there’s an interesting thread to be teased out here on the line between characters that players more or less create themselves from the ground up, all-but-complete pre-gens like those we did for the TEETH games, and this middle-ground of a really heavily authored characters that begin incomplete in play and provide a huge range of expressive possibilities, but nevertheless generate themselves based on the author’s intentions. That needs a bit of explaining, so I will try.

In The Between you do not do backstory at the start: you being mysterious is not just flavour, it’s core mechanism. As we play and are forced to “mask” the horrific results of failing checks in the dangerous Night Phase of the game, and so we fill out the story of our characters based on prompts that come with these masks. This is part of what I mean by it being authored: my character, the shockingly beautiful Alina Gray, was The Undeniable, and as such the prompts can only end up revealing her to be an awful person whose powers are woven with humiliation, exploitation and destruction of others, due to her (literally) towering narcissism. As we responded to the prompts and filled out the story of our characters so the true nature of these monstrous people were revealed.

This thematic core to the characters of course extends to their abilities: The Undeniable can choose to take any amount of punishment related to physical appearance, with a substitute artwork that depicts that character suffering the consequences, Dorian Gray-style. But they can also reveal side-characters to secretly worship them, pivoting the narratives for non-central NPCs up to and including destroying themselves. And The Factotum is bound to the character too, as we saw in the opening session, with both XP triggers and powers connected to this relationship of servitude. Not to mention the character’s other abilities bound to the house, their possibly extended lifespan, and those new powers we unlocked in play.

Oh man, we haven’t really even explained the house, have we? And I haven’t begun to scratch the surface of the other characters or why they were exciting in play. “A witch, a butler, and a Dorian Gray walk into a bar…” But I should let you get at a bit of that. As GM, you seemed to enjoy watching what was happening to these characters?

Kieron: It was a joy. Honestly, Alex’s Factotum being peak Butler could have been enough alone.

You pick up on the word “authored” above, which I think is interesting – that’s The Between, on a lot of levels. It narrows things – puts you Between it, if you will – which creates stages, both for players and GM, to fill. In fact, that’s one of the things I most wanted to see in play early on: specifically, how each character’s background is revealed in play via the prompts of the Masks Of The Past. These are a chain of prompts from which players make a kind of story based upon the type of character they are playing. The players are 100% completely barred from talking about their backstory, in any way. That’s such a strong and unusual prescription! Now, I’m echoing the game’s official line back at you, but I was interested to see what that gives you. For folks who want to build a character in advance, they get a chance to actually tell this stuff to an audience in play, an audience who are now invested in hearing what’s going on. And folks who just want to wing it, can do so. And as the Lost-derived elevated genre show so often leans on this quasi-mystery box stuff, having it integrated is just one thing about how the game gets about what it’s doing.

Jim: Right. There’s TV and cinematic devices in here.

Kieron: Side point – did you prep that stuff at all? Did you wing it?

Jim: I began by winging it, as is my wont, but it’s hard not to think about it as the game intensified, and I began to pick out ideas. If Gray had been around for a very long time, how long, and who had she encountered? I think the core thing about it for me was that it actually did the work of creating a character in a way that was a challenge rather than an invitation. You know, you might be invited to write a backstory for your character for a campaign, but here you have to do it within some narrow prescriptions: do it responding to the prompts, do it at the table in short enough time not to annoy everyone, do it in response to events, and so forth. And it also meant that the entire thing was a sort of creative discovery. Learning what an awful person I was really had a lot of energy to it! I suspected how terrible I would end up being by glancing at the playbook, of course, but I was discovering it along with everyone else.

Kieron: I loved seeing it all happen. It’s a game which gives a lot of agency to the players in terms of how they fill in their masks. The shape is a story, the details are yours. I let the masks happen, and took notes of the flashbacks, and looked to reintegrate what I could. We’ll come back to how much the game gives the GM as a palette, I’m sure, but I suspect you could run a pretty good game just with the way the Masks of The Past work.

Then there’s the Masks of the Present. These are a whole different bunch of story-kicking beats, as your characters cascade closer to gothic destruction. That the masks are mainly used in play for improving dice results (so most obviously avoiding player death) means you can see the romantic tragedies of them playing out. At least part of the fun of me being Keeper and watching it play out is that I studied everything else, but I didn’t study the actual player sheets in huge detail. I didn’t read all the prompts – so when Alex’s Factotum picked the mask of the present which revealed big chunks of his previous Masks of The Past were just a fake history? Well, I was surprised as everyone else. What a big narrative thing just to drop on the table. Also the gleefulness of just the “Most Beloved” one, which only one person at the table can pick, and then just deals with living rent free in all the Threats’ heads.

How did you find the use of the masks in play like that? I sense the goal is that we hit the dramatic moment, know how someone is going to die… and then we have the cinematic flashback to a crucial moment in their life, and play continues.

Jim: Winding things back a step, it’s interesting to see you say that you could run a game just off how the masks work. That was my takeaway too: that’s actually one of the most interesting mechanisms in the whole thing, and, for me, worked even better than the well-discussed Theorise move where the players are able to decide the nature of the mystery based on their interpretation of the clues (or other things too, in this game). In some ways I felt the even broader use of this mechanic in The Between to answer all kinds of questions, rather than something very focused like “who did the murder and why”, made it begin to feel less wieldy. There was so much going on, particularly when we were facing multiple threats at once, that building up a picture of events in your head was something of a challenge. Which is not to say that I didn’t appreciate the constantly escalating structure, because I absolutely did and I can’t remember a game we’ve played where things felt quite as climactic, but there were a lot of moving parts, and I think we all needed your sheet of paper with everyone’s names printed on.

: So just to reiterate my point about the masks: I could absolutely see a less involved story game that was based around the same sort of system, and that’s indicative of just how much is in The Between. In some ways it felt, to me, similar to when I first played Blades and read through and there were all these procedures and phases and having come from trad RPG I thought “how is THIS going to work?” And then I discovered that of course it did work really well, and the experience of seeing it all fall into place was incredibly compelling.

And to answer your question about the masks: I found them to be a lot of fun. Being despicable and knowing that it cast a shadow on how the other characters would respond to me was great. I rarely find myself getting into backstory all that deeply for characters I play and so being made to think about it was some excellent player enrichment experience.

But also I was a player here, and not a GM. And you were being thrown a bunch of curve balls by how much agency the game gives us the players, and had to track the generating threads, and moment to moment deal with the “actually it’s worse than that” consequences. Was the cognitive load a problem in The Between? Do you judge it better or worse to run that other comparable games? (Are there any comparable games?)

Kieron: Was the cognitive load a problem? I’ll answer that when my brain resets.

Kieron: It’s tricky to work out what to compare what GMing The Between to. The individual Threats are a little like the Mysteries from Brindlewood Bay. The deconstructed adventure model, where the various elements of the scenario are separated out and presented as a palette is akin to the Trophy games. And, of course, to be more literal, there’s plenty of comparable games: all the other Carved from Brindlewood Games that have followed The Between.

Where The Between differs from either Brindlewood or Trophy is that you’re not just running one adventure. You start with one in play. And then the next day, you introduce another one. That continues until you’re running three. Hell, maybe more will pop in if one of the playbooks introduces them, like Chris introducing The Coven, a witch organisation which his The Vessel character had ran away from. But when playing the game, basically, you’ll have three relevant sets of NPCs, clues and locations to keep in mind.

Due to the game’s day phase/night phase structure – which I’ll briefly explain as “by day, the players do what they want, by night, the Keeper fucks them up” – it’s not as if I can know for sure what anyone will do, so I have to keep everything in the possibility space. Plus, while the threats are separate, they’re all happening in the same city, so there’s always the chance of you wanting to cross the streams.

That’s a key thing – because even if a Threat is resolved, all those NPCs are still in London. Perhaps some of them have become side characters. Others are unlocked abilities. It’s all there. So you can never completely draw a line under anything, at least, if you want to do it well.

The running of the mystery space of these likely-three-threats-at-once is one thing – the game also has an eye on the larger campaign level, with a meta-Mastermind threat, which structures the whole game and gives a narrative shape to it, building towards a climax. Specific things unlock at certain points in the game, changing the shape of the game and producing genuine surprises. You pick up specific Mastermind clues when rolling particularly well, and it was always a panic for me when I realised I had to grab the Mastermind sheet to find the other set of clues I need to add to, as well as whatever I needed for the West End Wraith of whatever else we were up to.

In reality, I think I handled most of it okay. The point is there is so much stuff that there’s no way you could use it all. It’s an overstuffed menu, a palette with all the suitable gothic colours. Where I think I did worst was the Mastermind. That we were playing at a more accelerated pace than intended made me aware that I hadn’t done enough to establish the Mastermind as a presence and a person, and a genuine enemy haunting you and London via her proxies. Maybe I’m wrong at that – you’ll tell me – but I was aware I could have done better.

But still – I say that, and all the Mastermind level beats just hit. The moment when one of the Threats gets taken under her wing? Glorious. The assault on Hargrave House? I think that was one of the best things in the whole campaign.

In reality, what nags me about the game is an awareness that if I had slightly more brain than I have right now, I could have done it better. I think it may be the game the group liked most since Trophy Gold, right? Even with that, I’m aware that with a little more prep, or a little more time, I’d have taken it to a whole other level. Which is on me. But for a low-prep game, it absolutely rewards the prep you do. In the endgame, when I actually finally compiled all the names of the most important NPCs onto one sheet? Huge help.

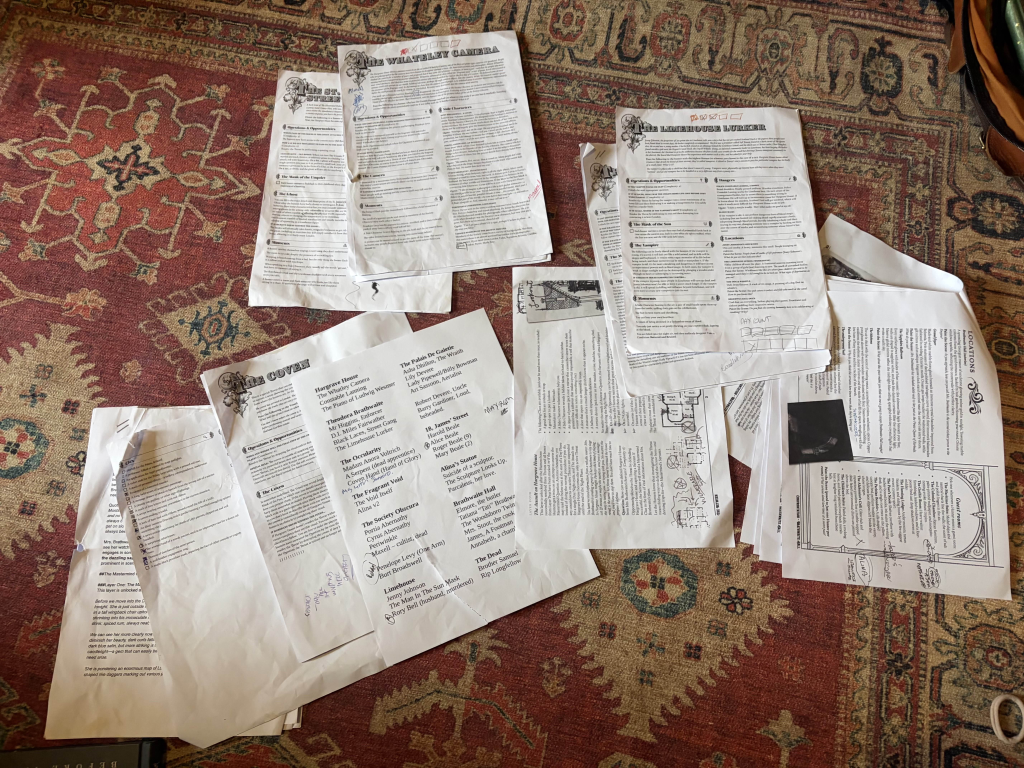

But, yes, The Between is a lot. These are the sheets I had scattered over my desk when running the game at the end. That’s every sheet I printed out, as there was never a point when I could know for sure I wouldn’t want to use something there again.

Kieron: I think that’s my takeaway: it’s a game that makes you look very good as a GM, if you just go with it. But it was a game which made me feel like I was failing it. You guys were thinking I was better than I felt I was. I think it’s very much a game that the more you give it, the more it’d give back.

Jim: In hindsight I can see what you mean about the Mastermind. I had felt like just getting no more than glimpses of them was intentional, but perhaps there needed to be a scene set and stakes defined? Either way the attack on the house and the final climactic episode both landed incredibly well, with imagery that teased and intrigued, and I think that probably was on you finding ways to tie it all together. (I also fucking love Sun Mask Guy, but that’s probably for an article on Best NPCs..)

Kieron: Oh, Sun Mask guy was a stand out. A random, almost unexplained NPC in an opium den, with the only “you die if you do this one thing” in the whole game… which you immediately did? You live for that.

Jim: There is nothing wrong with pushing the button that says DO NOT PRESS. I think that might be the point of RPGs.

Jim: And, most significantly, this is one of those occasions where I do not think anyone would have been unhappy for the campaign to have been longer or to have kept playing? The Between really did satisfying work on all of us. That other games were clamouring for our attention — yes, Mythic Bastionland, we’re coming to you — was the only reason I wasn’t asking for more. A rare thing, given our boredom thresholds.

Part of what commanded my attention was the way the phases gave a true rhythm to the game. Pausing and reflecting at breakfast, roaming around the city being nosy and rude during the day, having another moment to reflect and plan (and even activate specific powers) at Dusk, and then having to risk life and limb at night. It really gave the game a cycle, a beat. It is a clock ticking onwards, a pendulum swinging from safety into bloody danger.

And speaking of danger, we should get into how the Night Phase works. Like everything else in The Between it felt very structured, very authored. It works, as in the other games in the Brindlewood mold, as the bit of the game where you are genuinely in danger (“it’s worse than that”), but here it has a segmented spine in the form of “The Unscene”, where we would cut away from the action and narrate an unrelated dramatic or poignant sequence somewhere else in the city. The intention here is to look for “echoes”, where the action sequences echo what has happened in these narrative asides, triggering XP for us and just tying things up with a thematic bow.

What we should make clear about this is that it’s as intimidating as it sounds. Everyone approached this with trepidation: it was quite a demand to both fill out the prompt with perhaps a few minutes to think about it, and also deliver it in such a way as to make it coherent to find echoes in the action. In the end everyone did a sterling job of this, and there genuinely were moments where the echoes functioned as intended: I think of a scene where children living a hidden upbringing in the backrooms of a bordello played cops and robbers and drew their adventures on the walls, as my character toyed with actual policemen in the real world across the city.

So the phase had teeth not only in the sense that we had to burn masks for failed rolls because we were going to get mauled if we did not, but also in the sense that we really had to be switched on and engage not just with our own characters, but with painting the setting as a whole. The city ends up being a fabrication of the author, the GM, and the players together. I find that really engaging, because it’s making creative demands beyond that which most RPGs, that most creatively demanding of games, already does.

But there’s other stuff to consider in the Night Phase, too, especially from a GMing point of view?

Kieron: How the Night phase works was the element of The Between I was least sure about before coming into the game – and specifically how the Unscene works. The basic Night Phase I got – as you say, the game’s structured, but the Day Phase (powered mainly by the less-dangerous Day Move) is the closest that The Between gets to a traditional game mode. The players have control, moving freely in their investigation. The Night Phase is the GM’s phase. Sure, at the Dusk Phase the players say what they want to do, but that’s a desire or a plan. I could do anything from that point. You want to go and break into Braithwaite’s house? Sure, but on the way, the Limehouse Lurker is going to jump you. We go from there. That there’s a maximum of four sections of play for each character means that it feels feral: you hard cut between beats, and I know I have to get to a conclusion at the end. The Day is yours. The Night is mine.

Now, that I understood, and it worked as I hoped: it’s the hard-framing of PBTA turned up to the max.

But I just didn’t get the Unscenes.

Kieron: The Between is a cinematically inspired game, obviously, and tries to take structures of elevated genre television to hit harder. Cutting in montage between characters is a standard device, montage between characters entirely unconnected to the story simply isn’t. The game expressly wants nothing to connect to the players’ advenyures in this section. The Unscene is about populating the city. Which I get… but the way genre TV does that is in individual moments, not extended short narratives, and certainly not as regularly as the Between does. I thought the echoes were going to be hard, as I was worried it was something else I had to think about.

In practice, it’s not like that at all. I didn’t have to think about and that was the point. By definition, if it’s unconnected to the story, so nothing in its fiction will impact what I have to do. Echoes are for the players to watch out for, not me as GM. I don’t even know much about the aesthetic effect for you guys, because mostly I was using that narration space as a time to think about my next string of scenes, where I would hard cut to another character, and so on. I paid attention sometimes, but only after I’d done my next bit of mental improv prep. That’s interesting! I’ve never seen Cordova talk about this, so I don’t know if it’s his intent, but “creating a thing to maintain atmosphere at the table and let players have agency, but can be safely ignored by the GM if they have to think about something else” is one of the things in The Between which actually made it easier to run. The montage-GM style is something I’ve done a lot at, and think I’m reasonable at – but the Unscene let me really approach it with more consideration than I normally get to. It’s an fascinating idea.

We have gone on. You literally just messaged me saying “We’re now past 4000” words, which is a good time to start closing. That speaks to what the game is. It’s a lot, and a lot to talk about, and so we do talk.

In the same way I was buried alive between sheets, there’s whole sheets of stuff we haven’t touched.

For example, we’ve barely talked about its specific theme and setting: the ripe, sensual and deeply problematic 19th century. You are playing characters who are, at least in part, monsters, and certainly capable of doing monstrous things. People died. Lovers were killed by lovers whilst demonically possessed. People betrayed their families on your whim. The last thing you did was simply make a mother pass you their baby. You were going to try to save the child, sure, but that sequence was about as dark as a game gets. The Between is deeply gothic, and I’m aware that we could have gone even darker, more velvet draped.

It’s a lot, and so we can stop there, as no matter what we write, there’s more there in the ripe flesh. Between Heaven and Hell, there’s everything, and certainly including 4000 words and counting.

The Between is available from The Gauntlet.

Lost in the hills of Somerset, this Rossignol searches for meaning among the clattering of small plastic bones.

Leave a Reply