Or, to give it its true clickbait title, “Why I have absolutely no interest in running 7/9 of the games Quinns Quest has reviewed.”

You see, you can tell I’m a Jedi Knight Still Pining After His Age Of Lightsaber, because if I was properly clickbaiting I’d say “Why 7/9 of the games Quinns Quest has reviewed bore me to tears” but I can’t, because that’s not true.

They don’t bore me to tears. I watch them and think “that sounds great” or “Vaesen exists”. I love hearing Quinns talk about them. I love their strengths and weaknesses and ideas. I like to consider them. I would certainly play in a game of any of them, if there was someone who wanted to get them to the table.

It’s just that I have absolutely no desire to run 77.777 recurring of them.

There’s probably an essay on Quinns’ impact on the RPG scene – he’s essentially someone who has learned skills as an pop-critic in a more monied area and then brought them to bear in a medium where no-one has had the money to support the development of those skills. That’s when he launched Shut Up And Sit Down. And then he did it again, moving from the relatively bounteous space of Boardgames to indie rpgs. Indie-rpgs! No wonder he’s been a sensation. It’s like if Pele has turned up to your five a side kickabout, and asked if he can play.

However, seeing an old friend go out to bat for these games they (mostly) love has really made me drill down on my own tastes, and where they’ve separated, and ended up in a different place. If you’re reading this blog, I suspect it’s worth showing where my present biases are.

So… when I see a game, what makes me want to get it to the table? Why 7/9 of Quinns’ choices will be left on the shelf choke under the dust? What turns me on? What turns me off?

The most basic criteria is actually the easiest.

I will flick to a games’ average NPC stat block. I will compare it to the length of my index finger. The more knuckles it covers, the less chance there is I can be bothered. If the game assumes you need to know every random bozo’s ability to identify clouds, you can assume it’s way too much work for me to handle. Life is too short, and my index finger is too long.

This is what happened when I was going through a Runequest-curious stage a year or so back. I was thinking I could handle this, and then saw the NPC stat blocks and realised the level of detail for the lead characters was applied to everyone, and oh, no, definitely not.

None of Quinns seems to trip up on that – with the possible exception of Delta Green, but I’m not going to check that, as it fails on another count in a minute. Arguably Lancer, but that’s more a level of crunch generally.

The next step is actually it failing on strengths, not the weaknesses. The things which people say to excite you? In advertising or reviews? Sometimes they just don’t excite me. That’s not a problem. They excite a lot of people. If you did math, I suspect I’m in the significant minority. That’s fine, but it’s also true.

The first of these is that the game’s strength is outside the game itself. The game is primarily a serving device into which the real appeal is poured: the setting, scenarios, or campaigns.

No interest whatsoever. This is where Delta Green drops. This is where Mothership drops. This is a core one for me, and should be considered foreshadowing of where this is going.

The second is that a game’s appeal is who you are playing or the world you’re exploring. Some really cool fiction, or unusual characters. Maybe we’re dimension skipping Jet-Set-Radio-esque teen adventurers? You in?

Nope. More interest, certainly, but not enough to make me wrestle with my google calendar and see when the nerds can all hang out. Most of them go here: Slugblaster, the Wildsea, even Triangle Agency starts to wobble.

Third, if your game does something really cool in session eight, I’m out. This is an extension of my aesthetic as a videogame journalist – if your game gets good after twenty hours, it sucks. This isn’t exactly 1:1 that, but if a key element which makes the game interesting is way off? No, I’ll spend my time on a game which excites me from session 1, thanks. So Triangle Agency bounces into the void.

(I suspect I’ll be playing that one in the new year – looking forward to it. But I just won’t run it, guys.)

Which leads to what does excite me?

I realised it was pretty simple.

It’s whatever the thing which I tell you excitedly whenever a game is mentioned.

It’s always a single fact.

This article was originally going to be a list of these one cool things. But since then, I realised that my 101 Favourite Games Ever series is going to touch on a bunch of them, so I don’t want to repeat myself.

But anyway. A single fact. And with my present tastes, it’s probably a mechanic. It’s not always a mechanic, but usually is.

I am firmly of the corner that a system that gets out of the way can just get out of my way. The only point of a system is that it takes me to a place where I wouldn’t reliably get to by myself.

This certainly includes an element of formalist neophilia: I just like new ideas I haven’t seen before. However, it’s not just that. I have no interest in games which change mechanics to something novel for the sake of it, as if cool math is a turn on. This isn’t boardgames.

What I am mainly interested in is a mechanic which shows profound understanding of the fiction of the game, and has been designed to enable and magnify that fiction.

You see, you can throw a huge world of cool stuff at me, but I’m going to be taking it on faith you actually understand what any of it means. What a mechanic does is show that you understand your fiction, as you are capable of abstracting it.

The second I see a mechanic which does, I can trust the book. If I’m going to spend time with it, I need that. It excited me, because I feel safe, and I feel excited as I can see the implications of a mechanic spinning off into play-space.

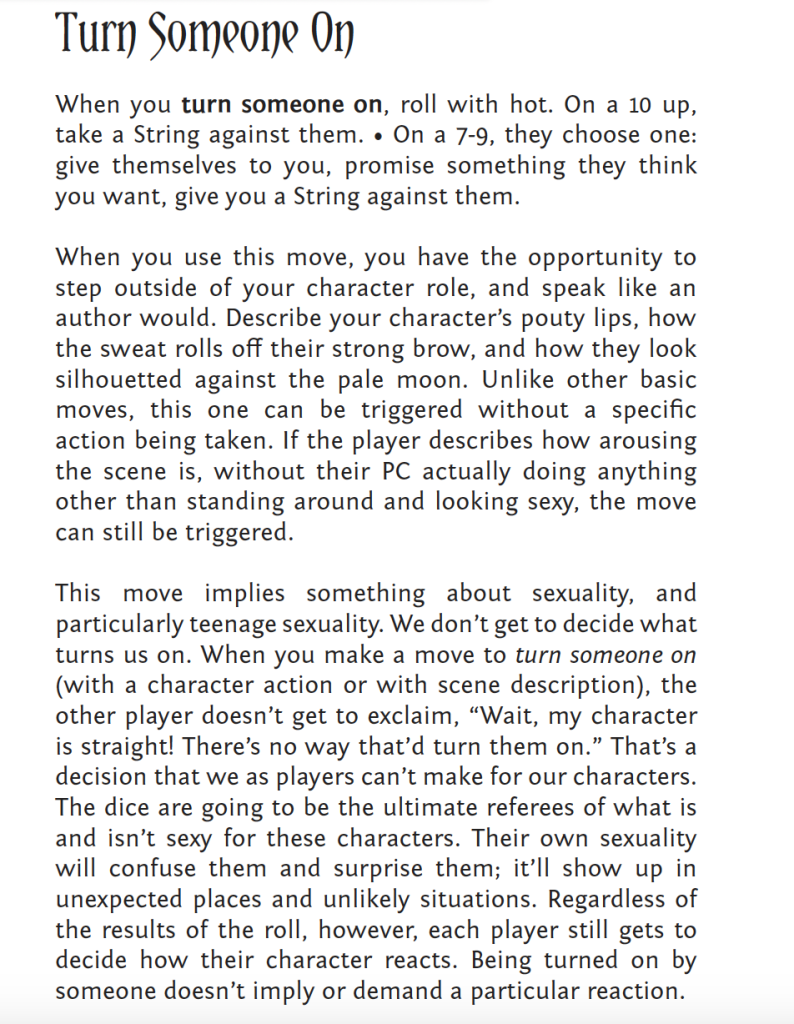

My indie-TTRPG journey really started with Monsterhearts. Why was I attracted, when I spent the 90s dodging playing World of Darkness. Yes, I’m a (blood)sucker for a more explicit queer theme, but that certainly wouldn’t be enough for me now.

But even over a decade on, I read this…

…and I’m as all in as I ever was.

This absolutely understands something about its genre, and has created a mechanic to ensure it happens. This is a story about people’s messy, confused sexual awakening, and you can’t run from it. The game won’t let you.

RPG critic sorts may have sensed I’ve been resisting mentioning System Matters, even though it’s floating there. I don’t need to go that strong, even though I clearly have sympathies for that position. I don’t think it matters most, but it’s certainly there.

I’m also aware that my neophilia may be biting me with some of the above – there’s mechanics in the games I’ve rejected which certainly show how the games understand their genre. But, at least in terms of what I’ve seen, they’re not the incandescent brightness of Turn Someone On. There’s an implicit caveat there – in that if I actually went through myself maybe I’d find one, as it’s what I care about most. Perhaps if my copy of Slugblaster wasn’t stole on the train to Sevenoaks I’d be writing a different article?

Which leads to the two of the nine I am attracted to.

Firstly, Heart. I’d already ran Heart, and it exists as the meniscus between what I think primarily interests Quinns and what primarily interests me – it’s got all this berserk worldbuilding and excellent classes and all that for him, and for me, it’s got the Beats system which turns Stars & Wishes into both the GM prep and the XP system.

And then there’s the second game, Mythic Bastionland.

You know from The Skim that Jim and I dig its vibe from across the bar. I actually include the One Thing I Tell People About Mythic Bastionland in that feature.

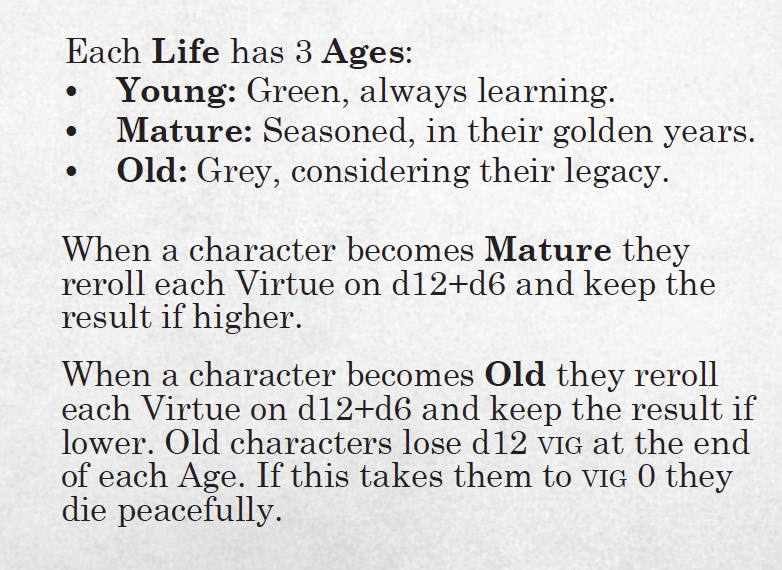

It’s this rule…

Why on Earth would the ageing rules excite me?

Firstly, they’re just beautiful. People may improve from their youth. People age in an unpredictable, but inevitable fashion. People die. They change meaningfully, with a few moving parts. This is a designer who really knows what they’re doing.

Secondly, it also shows exactly how Mythic Bastionland knows how to engage with its theme. It’s a micro-Pendragon, doing a story about knights adventuring across a longer time period. As such, it wants to compress some of the thrills of the Great Pendragon Campaign‘s 80-year 100-odd-session game into a OSR-format.

That it’s a game of dynastic knights fighting myth means that the ageing rules are just a great test for how well McDowall gets it.

He clearly does, and I wish I could play a game of it right now.

Which is lucky, as our Mythic Bastionland campaign starts tonight.

We will report back, and probably go on about the ageing rules some more. They’re nifty.

Kieron Gillen lives in Bath, for a certain value of the word “lives”.

Leave a Reply